Blog Archives

The Military Air-Scouts (Vitagraph, 1911)

The Military Air-Scouts (Vitagraph, 1911)

Directed by William Humphrey

Starring Earle Williams and Edith Storey

So this is a curious one, not so much because of the plot (what little there is of it) but because of the timing.

Lieutenant Wentworth (Earle Williams) is in love with Marie Arthur (Edith Storey) and hopes to marry her. When war is declared between the United States of America and the United States of Europe, he accepts a dangerous air-scout commission. After successfully sinking the enemy’s fleet of battleships, his plane is shot down. The lieutenant, not badly hurt, returns home and finds Marie ready to marry him.

Now, I’m reading a lot into the story that is never actually portrayed on the screen—especially when it comes to Marie and Wentworth’s motivation—but I think that’s the essence of the plot.

Not dissimilar to The Victoria Cross, you might be saying, but whereas the Crimean War had already happened prior to The Victoria Cross’s release, not so for The Military Air-Scouts and the First World War. Air-Scouts, released in 1911, is set in the not-too-distant future of August 4th, 1914. For those playing along at home, it might interest you to know that Franz Ferdinand was assassinated on June 28th of that year.

Did ancient aliens write this scenario or is it simply indicative of the feeling at the time that the Balkans were a powder keg and war was sooner or later inevitable?

Also interesting to note that the stunt pilot actually flying the plane is a young Henry “Hap” Arnold, who would later become both General of the Army and General of the Air Force in the Second World War—the only man to be a five-star general of two different military services.

My rating: This is a very, very slight film, but I like it purely for the miniatures in the naval battle scene.

Available from Harpodeon.com

Jane’s Bashful Hero (Vitagraph, 1916)

Jane’s Bashful Hero (Vitagraph, 1916)

Directed by George D. Baker

Starring Edith Storey

I’ve said in the past that the release notices placed in trade magazines don’t always correspond in every detail to the film as it was actually released, but I don’t think any that I’ve worked on are quite so different as Jane’s Bashful Hero. First, let’s look at its synopsis in Moving Picture World:

Bashful Willie Wiggins courts Jane Brown, the village belle, but after nearly wearing out the sofa cannot find the courage to pop the question. Jane finally resorts to the old ruse of jealousy. That night the village folks of Mudville are scandalized to see Jane in the arms of a stranger silhouetted against the window shade. The whole town rises up in protest, and Willie, backed by the minister, demands an explanation of Jane. She guiltily denies the impeachment and the crowd, calmed by the dominie, disperse, but Willie camps on the doorstep to catch his “rival.” Jane during the night regrets the scandal her little trick caused and flings the dummy she used into the well. Willie sees this and is horrified, believing it is the body of his rival, whom Jane has murdered. Frantic with excitement, he arouses the whole village. The indignant mob rush to Jane’s home in their nighties and drag her forth dramatically. The sheriff goes down the well, and of course Jane has a good laugh on them all when the dummy is hauled up. Willie now realizes the depth of Jane’s love and pops the question right then and there

That’s almost but not entirely different from Paul West’s shooting scenario for Jane’s Bashful Hero. There’s enough similarity that I don’t think it’s describing an entirely different film, but only just.

Jane Brown (Edith Storey) is a rather homely young woman—looking rather disheveled with messy pigtails and missing a front tooth—and the townspeople regard Willie Wiggins (Donald MacBride) courting her as very much of a joke. Indeed, they gather round to point and laugh at them when they’re together, causing Jane to chase them off, swinging her broom like a sword.

But Willie is too bashful to propose. Conversely, Dutch Louie (Billy Bletcher), the town’s grocer, is anything but bashful. He’s courting her aggressively and would marry Jane that day if she would have him, but she won’t. She wants Willie.

She reads in the newspaper that the way to a man’s heart is through his stomach, so she plans a dinner and invites Willie over. The meal starts well, but Jane’s playing footsy embarrasses him to such a degree that he confuses the table cloth for his napkin, tucking it into his shirt; and when she begins stroking his hand, he abruptly stands up, pulling Jane’s dinner onto the floor. Mortified, Willie flees from the house.

A gang of kids is forever pulling nasty practical jokes on Jane. She shoos them off when one of them dresses as a mustachioed home intruder. Leaving the mask behind, Jane gets an idea: maybe the way to spur on Willie is to make him jealous. With the mask and some old clothes from the attic, she builds a scarecrow rival, which both Willie and Louie see Jane petting and kissing in silhouette on the window shade that night.

A detective from the big city arrives in town with a wanted poster for Banker Bill, the notorious and at large bank robber. It isn’t him, but he looks rather like Snub Pollard, with a large mustache as his defining characteristic—just like Jane’s scarecrow. Willie and Louie both see the poster and react accordingly: Louie reports to the constable (Edward Elkas) that Jane is harboring the fugitive, hoping to dispose of his rival, while Willie rushes to Jane to tell her that the coppers are out to arrest Banker Bill and she had better hide him.

Jane dumps the scarecrow down the well, which Louie spies from around the corner. The constable, looking to impress the detective, comes to arrest Jane when she won’t say where the fugitive is hiding. Willie, meanwhile, dumps a bottle of ink on his face and fashions it into a crude mustache, parading in front of the constable and pretending to be Banker Bill. The constable isn’t fooled. Louie tells them he’s really hiding down the well. They pull up the bucket, and with it, the scarecrow. In shock, Louie falls down the well himself, and Willie, just now discovering his initiative, finally proposes to Jane.

So, as I said, there are enough similar points in the Moving Picture World synopsis that I don’t think it’s summarizing a different film altogether, but the overall plot it describes is vastly different from the real Jane’s Bashful Hero.

The real Jane is a fun enough film, though. Very well edited, and as always, Storey is a remarkably fine actress.

My rating: I like it.

Available from Harpodeon.com

The Dust of Egypt (Vitagraph, 1915)

The Dust of Egypt (Vitagraph, 1915)

The Dust of Egypt (Vitagraph, 1915)

Directed by George D. Baker

Starring Antonio Moreno and Edith Storey

In the past, I’ve briefly touched on 9.5mm home movie abridgments sometimes representing all that’s known to survive of a film and how these abridgments are by and large ignored. It was the policy of some archives until rather recently to dispose of all their holdings of a film if any part of it showed decomposition — it’s little wonder these abridgments that are, by nature, incomplete would be beneath notice.

Some films are represented in an even more slight degree. Expensive crowd scenes may have been cannibalized in the sound era for stock footage — a bit of The Battle Cry of Peace survives for that reason — or they may have been lampooned in shorts like the Fractured Flickers series. To the transitional generation, who lived through the talkie revolution, silents were not only old hat — they were embarrassments — things that were only suffered to exist that they might be mocked.

About two and a half minutes of The Dust of Egypt survives by way of The Movie Album, a 1931 Vitaphone short. The Movie Album wasn’t as entirely derisive of its subject material as Fractured Flickers — not entirely.  The clip actually represents a few fragments as the excerpt snips out quite a bit of material within itself, but all are from the climax, just before the ‘it was all a dream’ reveal.

The clip actually represents a few fragments as the excerpt snips out quite a bit of material within itself, but all are from the climax, just before the ‘it was all a dream’ reveal.

Geoffrey Lascelles (Antonio Moreno) has just proposed to Violet Manning (Naomi Childers) and she’s accepted. After a night of celebration, Geoffrey stumbles back home to sleep off his intoxication. Enter Simpson (Charles Brown), Professor Johnson’s assistant. The Professor is on a dig in Egypt and sends back a mummy, but the museum is closed and Simpson wants to leave it with Geoffrey until morning.

In his dreams, Geoffrey envisions Ameuset (Edith Storey), a princess of Egypt. She’s bored with life. Her magician, Ani (Edward Elkas), offers her a love potion that cannot fail, but the Princess demands something new. He instead presents a potion that will transmit her through time — thousands of years into the future — to an age entirely unlike their own. She’ll find love there, he promises, and kiss but once, for the second kiss will make her “as the dust of Egypt”.

Startled awake by a sound in the sitting room, Geoffrey goes to investigate. He finds the mummy quite alive and it is the very princess of his dreams. She at first believes he is a magician like her own Ani, in that he commands light at the flick of his finger, but she soon finds amusement with modern technology — the seltzer bottle, especially, entertains her to no end.

a magician like her own Ani, in that he commands light at the flick of his finger, but she soon finds amusement with modern technology — the seltzer bottle, especially, entertains her to no end.

Afraid of what it would look like to be found alone with a strange woman late at night, Geoffrey does the first thing that comes to mind and calls the Mannings. Violet is put out. Geoffrey’s tale of five thousand year old Egyptian princesses does not strike her as terribly credible, and as he has no other explanation for Ameuset, she returns his ring.

Violet provokes a rather extreme degree of jealousy in Ameuset. Geoffrey might not love her, but she’s surely taken to him. Suddenly she recalls Ani’s love potion and dumps it in Geoffrey’s glass. True to the sorcerer’s word, Geoffrey at once falls passionately in love with the Egyptian princess. The second kiss — —

Benson (Jack Brawn), Geoffrey’s butler, startles his master. He’s sorry to wake him so early, but a gust of wind tipped over the sarcophagus (or “the blooming mummy case”). Geoffrey inspects it to find it contains nothing but a desiccated mummy quickly turning to dust.

I have so much fun with reconstructions. I didn’t do a full one with The Dust of Egypt partly because there’s so little surviving footage and partly because I was working from an extremely limited number of stills. Most came from the novelization in Motion Picture Magazine, a couple from trade magazines, and a couple more from lobby cards I have. They were just about enough to present the story in a condensed form not much more elaborate than the summary above — to provide context to the surviving fragments and not strive far beyond that.

I have so much fun with reconstructions. I didn’t do a full one with The Dust of Egypt partly because there’s so little surviving footage and partly because I was working from an extremely limited number of stills. Most came from the novelization in Motion Picture Magazine, a couple from trade magazines, and a couple more from lobby cards I have. They were just about enough to present the story in a condensed form not much more elaborate than the summary above — to provide context to the surviving fragments and not strive far beyond that.

I can’t in good conscience give a rating. I can hardly tell what sort of a film it was from two and a half minutes of footage and a handful of stills. As it reads, the plot is pretty well bog standard for a mummy come to life comedy, but a well tread plot doesn’t mean the film couldn’t have tread it well. I like Edith Storey — I’ll say that.

Available from Harpodeon.

A Florida Enchantment (Vitagraph, 1914)

A Florida Enchantment (Vitagraph, 1914)

A Florida Enchantment (Vitagraph, 1914)

Directed by Sidney Drew

Starring Edith Storey and Sidney Drew

My look at silent films with gay themes continues with a “farcical fantasy” released in the summer of 1914:

Lillian Travers (Edith Storey) is a New York heiress whose fortune has just been turned over to her. Seeing nothing left to stand in the way, she jumps on the train to Florida to surprise her fiancée and begin arrangements for their wedding. His name is Fred Cassadene (Sidney Drew); he’s the house doctor at the exclusive Hotel Ponce de Leon in St. Augustine. Staying at the hotel is a flirtatious young widow, Stella Lovejoy (Ada Gifford), who delights in feigning illness for the doctor’s attention. When Lilly arrives, unannounced, she’s furious to find Fred and Stella apparently hand-in-hand in the hotel courtyard. Fred explains and Lily is placated… for the moment… but it seems something keeps coming up between Fred and Stella and Lilly’s suspicions heighten.

While all this is playing out, Lilly is staying with her spinster aunt, Constancia Oglethorpe (Grace Stevens). Connie is of old Southern stock and she tells Lilly the story of one of her ancestors, Captain Hauser Oglethorpe. It seems he was shipwrecked off the coast of Africa (the implication is that he was a slaver, although that isn’t explicitly said) and came away with a mystery: a box, now on display in Connie’s parlor, containing an enigmatic note that reads “In the duplicate of this casket, whereabouts unknown, lies a secret for all women who suffer.”

Lilly goes out with Bessie (Jane Morrow), the daughter of Connie’s widower neighbor Major Horton (Charles Kent), to hit up the local antique stores. She finds a box that looks just like her aunt’s, with a tag that claims it was found washed ashore a century ago. Lilly buys it and, from its contents, learns the rest of old Oglethorpe’s history: after the captain was shipwrecked, he was rescued by an African tribe that was curiously all male. The chief of this tribe, Quasi, told him that they recruited their numbers from the women of neighboring tribes. These women they fed a particular seed, which instantly changed them into men. Quasi gave Oglethorpe four of these seeds as a parting gift – Lilly finds the vial containing them in the box.

After the final straw breaks Lilly’s trust in Fred’s fidelity, she swallows one of the seeds. She grasps at her throat as it begins to take hold then, after a moment’s pause, stands up, hurls away the chair, grabs the box and remaining three seeds, dashes Fred’s flowers to the ground, and marches out of the room.

Lilly spurns Fred at the ball and begins courting Bessie. After a while, she gives a seed to her maid and the two return to New York to complete their transformation: Lillian Travers becomes Lawrence Talbot and Jane the Maid becomes Jack the Valet. Lawrence again visits Florida, this time to ask for Bessie’s hand in marriage…

A Florida Enchantment (1914) was adapted from a Broadway play of the same name, which in turn had been adapted from a novel by Archibald Clavering Gunter. The film is more popular now than it was when it premiered – audiences and critics alike panned it for being too absurd. In truth, it was never intended to be a hit in America. Like many of Sidney Drew’s “sophisticated comedies”, Vitagraph was banking on its assured success in France to buoy lackluster domestic returns, but unfortunately the First World War broke out during production and that market was cut-off. Enchantment lost Vitagraph a fair bit of money.

It’s interesting to see the dichotomy of reactions the film shows between same-sex attractions. When Lilly (still outwardly female) openly flirts with Bessie, Connie is a bit scandalized and Fred looks on in confusion, but there is no uproar. No one attempts to stop her, nor is she so much as criticized for her actions. When later in the film Fred swallows a seed and begins to act femininely, and angry mob literally chases him off the end of a pier and into a watery grave. It’s played for laughs in Enchantment, but you’ll see it repeated in serious dramas as well: gay women might get off lightly, but gay men have to die. Paul Körner, Claude Zoret, Franz Sommer – I can’t think of a single lead character who breaks this trend.

I like A Florida Enchantment a great deal. It was actually the movie that got me interesting in releasing my film collection on video and it became my first DVD. I’m presently working on it again and hope to have a new version out for its hundredth anniversary next year (and maybe a theatrical screening or two – we’ll see what the card’s hold). It’s a better transfer and the restoration software I’m using is much improved. There’s still a long way to go, but I’m already proud of it. Here’s a sneak peak of the new video:

My rating: I like it.

Available (old version now, new one sometime next year [or several years – I am late sometimes]) from Harpodeon

Launching an extensive 2K remastering of A Florida Enchantment. Read my log on it here.

When the Tables Turned (Star Film, 1911)

When the Tables Turned (Star Film, 1911)

When the Tables Turned (Star Film, 1911)

Directed by William F. Haddock

Starring Edith Storey and Francis Ford

Ethel Kirby (Edith Storey) is a New York actress on vacation in Texas. On the train to Lariat, she meets Florence Halley, who’s also on her way to Lariat to visit her aunt (Eleanor Blanchard). Halley had often lamented to her aunt how the days of the Wild West were over and the cowboys had been tamed, so as a surprise, her aunt has arranged a little reenactment of the old days for her return. The ranch foreman (Francis Ford) has organized his ranch hands into a posse and intends on kidnapping Halley from the stagecoach, but they mistakenly take Kirby instead. Kirby is locked in a barn and at first believes she’s actually being held hostage, but then she overhears the ranchers talking about how well the show is going and realizes that it’s all an act. She decides not only to play along, but to use her superior acting skills to outfox her pretended captors.

The premise, that of a civilized, modern West play-acting its wilder past, would become a very common trope in the later 1910s (there’s even an episode of The Perils of Pauline (1914) that starts out with exactly the same faux-kidnapping setup seen here), but When the Tables Turned (1911) is certainly the earliest film example I know of it.

Edith Storey, as always, is excellent in her performance. She’s a remarkably versatile actress, quite capable of playing one role, then taking on another with entirely opposing characteristics, and managing to portray both with equal conviction and believability. It’s a quality essential to making Kirby work here, as she has to go from a damsel in distress to an apparent madwoman to what I can only describe as a vindictive puppetmaster in the span of a few minutes. A lesser actress I don’t think could pull it off at all, much less make it seem as natural as Storey does.

I enjoyed the film and would recommend it.

My rating: I like it.

Available (sometimes) from Texas Guinan

The Victoria Cross (Vitagraph, 1912)

The Victoria Cross (Vitagraph, 1912)

The Victoria Cross (Vitagraph, 1912)

Directed by Hal Reid

Starring Wallace Reid and Edith Storey

Lieutenant Cholmodeley (Wallace Reid) is in love with the Colonel’s daughter, Ellen (Edith Storey), and wants to marry her, but her father (Tefft Johnson) won’t allow it until Cholmodeley has “earned his spurs”. War has just been declared between Britain and Russia and the Lieutenant and Colonel are called to the Crimea. To be nearer her love, Ellen joins Florence Nightingale (Julia Swayne Gordon) and follows the troops as a front-line nurse. There, she witnesses the charge of the Light Brigade, where Cholmodeley distinguishes himself by rescuing a fallen comrade and fighting off several Russians in the process. Back in England, he’s awarded the Victoria Cross by the Queen (Rose Tapley) and the Colonel gives him his consent to marry Ellen.

The Victoria Cross (1912) is an excellent example of a “quality film”, a curious genre that emerged and disappeared in the early 1910s. Describing what a quality film is and why they came into being could fill whole books (and, indeed, it has), but in the briefest terms, a quality film is a movie with a historical, biographical, or literary nature viewed through an American moral lens intended to be watched by recent “undesirable” immigrants (Jews, Italians, Poles, etc.) as a means of uplifting and Americanizing them. Further, although they were never the target audience, the mere existence of quality films acted to legitimize motion pictures in the eyes of the upper classes, who until that time looked at them with xenophobic suspicion (cinema tickets were affordable even for the lowest rungs of society and the silent drama does not require one to understand English, you see). Nearly all the major studios made at least a couple, but Vitagraph was the undisputed champion of the quality film. The Victoria Cross ticks all the right boxes and would have met with the approval of the “uplifters”, but what’s slightly unusual for the genre, it’s a pretty well-made and entertaining film, too.

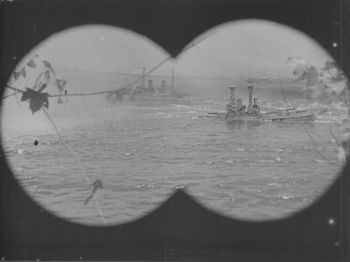

One thing that impressed me was how it handled the charge of the Light Brigade itself. Rather than portray the charge directly, it’s shown from Ellen’s perspective, back at camp through binoculars. It’s a novel device that allows the film to focus on individual snapshots of the battle, making it seem like they must be taken from a much larger picture. The film already has a large cast, with 80-100 extras and half as many horses, but only seeing them in close-up through the binoculars, it seems truly massive. It’s easy to believe that you’re actually watching 600 mounted men charge against the cannons. Compare The Victoria Cross to something more conventionally staged, like The Battle (1911), and you’ll see what I mean.

And it’s just super fun in an action movie sort of way. When Cholmodeley charges in to save his fallen comrade on the field, he’s rushed by three enemy soldiers that he fights off with his sword. The last he lifts up in the air, over his head, and then slams into the ground. We cut back to Ellen, and when we return, there’s a whole pile of bodies at his feet. I will say that the film starts off a bit slow, but once the battle is underway, it’s incredibly entertaining.

My rating: I like it.

Available from Harpodeon