Monthly Archives: July 2014

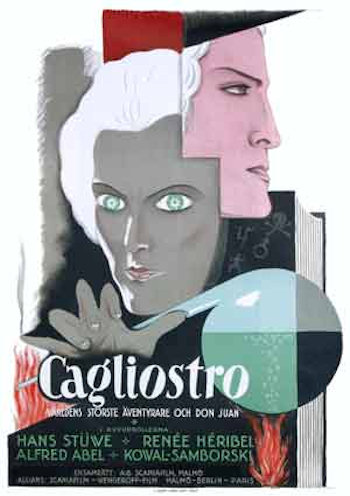

Cagliostro (Albatros, 1929)

Cagliostro (Albatros, 1929)

Cagliostro (Albatros, 1929)

Directed by Richard Oswald

Starring Hans Stüwe

“Long thought to be lost…” the back of the DVD case says, although that’s a slight exaggeration. The original theatrical release was ten reels long, which would play for a bit under two hours. That version was and still is presumed lost, although a few fragments from it have turned up and have been incorporated into this video. The bulk is sourced from a home movie version released on 9.5mm in 1931, which has never been unavailable on the collector’s market. As was common for 9.5mm, the film was abridged. The Cagliostro home release filled three super reels. For reasons I won’t get into, it’s hard to say exactly how long that would run (it depends heavily on how many title cards there are), but it would be somewhere between 40 and 60 minutes. The video, which again has a few additional clips from other sources, is just under one hour long.

So, about half of the footage is missing. Subplots and non-essential characters are excised, and the main plot is streamlined and elided in places. Allowances must be made when watching it for punctuations in continuity.

It’s the time of Louis XVI. Joseph Balsamo, Count Cagliostro (Hans Stüwe) — “healer, necromancer, founder of sects, and gentleman of fortune” — is the talk of Paris. His wife, Lorenza (Renée Héribel), is worried. Cagliostro’s life as a showman is a precarious one.

Cagliostro stumbles upon Jeanne de la Motte (Illa Meery), a woman who, though impoverished, is of royal blood. He sees in her his ticket to the court. He spruces her up á la Eliza Doolittle and she’s introduced to the Queen (Suzanne Bianchetti), who takes her on as a handmaid.

For her part in the bargain, Jeanne uses her newfound influence to get Cagliostro an audience with the King (Edmond Van Daële). The King expects to be entertained by a charlatan’s magic tricks, which offends Cagliostro. He refuses to transmute lead into gold for anyone who doesn’t believe. Instead, he reads the Queen’s fortune. Marie-Antoinette, he says, will soon follow her husband to the guillotine.

Cagliostro takes an active role in ensuring that his prophesy comes to fruition. A necklace worth 2,000,000 pounds had just been offered to the Queen. She refused it. With that money, she said, France could build a warship, and France needed warships more than she needed a necklace. Very selfless, but counterproductive to Cagliostro’s aim.

The Prince of Rohan (Alfred Abel) is secretly in love with the Queen. Cagliostro, with the help of Jeanne, makes Rohan believe that his love is not unrequited. In a forged letter, the “Queen” directs Rohan to buy the necklace for her. Rohan puts down the first installment for the necklace and, with his heart all a-flitter, hands it over to the veiled woman in the palace garden.

The Affair of the Diamond Necklace (a real-life event, which happened not too unlike its portrayal here) is a disastrous blow to the public image of Louis XVI. Within the court, it’s soon found out who’s to blame and Rohan, Jeanne, and Cagliostro are arrested. Popularly, however, Marie-Antoinette is blamed for masterminding everything.

Cagliostro escapes with his wife Lorenza and they flee to Italy. The Inquisition was waiting and sentences both of them to death for practicing black magic. At dawn, Lorenza is the first marched to the scaffold. Cagliostro watches as the hangman puts the noose around her neck. Just as the rope goes taut, he deftly grabs a sword from one of the guards and cuts Lorenza down. The bottleneck of steep, narrow scaffold stairs limits the number of guards Cagliostro has to defeat, and he and wife manage to escape once again.

On the road, they meet a gravedigger at work and ask whose grave he’s opening. “The notorious Cagliostro’s”, he says, “and who are you, sir?” Cagliostro replies “I am he who is”.

Cagliostro was acclaimed as a swashbuckling epic, but there are only two action scenes included here. The abridgement focuses most of its runtime on the Affair of the Diamond Necklace. It has the cinematography of a late silent picture, with a style that’s a melding of German and French. I’ve heard director Richard Oswald’s early films described as “workmanlike”, but I don’t think any would deny the artistry of his later silents. Ever since Lucrezia Borgia in 1922 and particularly Carlos and Elizabeth in 1924, he had a fondness for tracking shots, and they are extensively used in Cagliostro. (His later American talkies might be called “forgotten” — although his son, Gerd Oswald, had a reasonably successful directorial career on TV).

I had high hopes for Cagliostro and I wasn’t disappointed by it. I found it to be thoroughly enjoyable, and would recommend it.

My rating: I like it.

Available from Potemkine

La Maison Ensorcelée (Pathé, 1908)

La Maison Ensorcelée (Pathé, 1908)

La Maison Ensorcelée (Pathé, 1908)

Directed by Segundo de Chomón

To begin with, Segundo de Chomón’s La Maison Ensorcelée (1908), or “The Enchanted House”, is a beat-for-beat rip-off of J. Stuart Blackton’s The Haunted Hotel (1907). There’s long been confusion about who was stealing from whom, as the film is often misidentified as La Maison Hantée (“The Haunted House”), which Chomón made two years before in 1906. Hantée is presumed to be lost — however, reading its plot synopsis or just looking at the recorded run time will tell you that Hantée had to be an entirely unrelated work.

Three people, evidently traveling across the countryside, are caught in the rain. They spot a house that, frankly, doesn’t look too inviting. Between bolts of lightning, a trio of witches can be seen flying through the sky. One bolt strikes the house and it’s transformed into a googly-eyed face.

Inside, the travelers are immediately taunted by spectral beings of various sorts — finding their belongings moving around on their own, and their coats and hats standing up and walking away. They sit down to a meal. A knife lifts itself and slices the sausage and bread. The cups slide into place and an invisible hand pours out the coffee and drops sugar cubes into each.

It turns ugly when the house starts spinning and the travelers are flung to the ground. They seek shelter under the covers of the bed, but the back wall fades away and a giant demon appears that sweeps them up in one hand. In the forest, he leaves them dangling from a high tree branch.

The only significant change in the story between La Maison Ensorcelée and The Haunted Hotel is that, in the latter, there is only one traveler rather than three. The plot and visuals used are otherwise near identical. With that said, Ensorcelée is an enormous technical achievement that surpasses Haunted Hotel in almost every aspect.

To give only one example: In Haunted Hotel, the stop-motion animated food sequence (which the film is most known for) is one, uninterrupted medium-shot of the table. When it’s over, it pans to the traveler, who we can only assume was watching. Ensorcelée cuts to a reaction shot partway through the sequence, and at the end, the travelers lean into the frame in the same arrangement they were in previously, letting us know that they were there the whole time and saw all that we saw. It’s really not much at all, but it’s a little touch that makes the film play so much better.

I liked La Maison Ensorcelée (1908). It’s a flagrant rip-off of Blackton’s film, but it’s hardly the only example of one filmmaker mimicking another’s success in the early silent era, and unlike, say, Lubin’s Great Train Robbery (1904), I think this one actually improves on his model.

My rating: I like it.

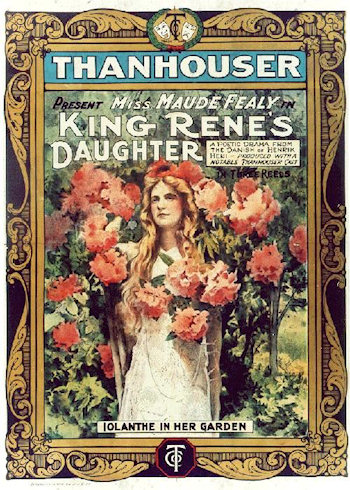

King René’s Daughter (Thanhouser, 1913)

King René’s Daughte r (Thanhouser, 1913)

r (Thanhouser, 1913)

Directed by W. Eugene Moore, Jr.

Starring Maude Fealy

Just after her birth, Iolanthe (Maude Fealy) is engaged to Tristan (Harry Benham) as a political alliance between her father, King René (Robert Broderick), and his father, Count de Vaudemont (Leland Benham?). Shortly thereafter, a fire breaks out in the palace. Iolanthe is rescued, but is for whatever reason now blind. Ebn Jahia (David H. Thompson), Moorish mystic, divines her future and says that, so long as she never knows that she cannot see, her vision will return on her sixteenth birthday.

Iolanthe is raised in isolation, hidden away in a small cottage inside a walled garden. She and Tristan have never met. As the scheduled wedding date approaches, Tristan — “hating the woman he has never seen” — runs away. He finds his way into the garden and discovers Iolanthe without realizing who she is. Tristan falls in love with Iolanthe and begs King René to break the engagement to his daughter so that he might marry her. King René reveals that Iolanthe is his daughter.

Iolanthe’s nurse (Mrs. Lawrence Marston) is worried that Tristan gave away Iolanthe’s blindness and that now she will never see again. Tristan did figure it out after Iolanthe was unable to distinguish a white rose from a red one, but he also figured out that Iolanthe apparently didn’t know that she couldn’t see and did not say anything about it. At the end of day on her sixteenth birthday, Iolanthe recovers her vision and everyone lives happily ever after.

There are subplots I’m not super clear on and details that seem to be relevant but damned if I can tell you why. The film is based on Henrik Heri’s then-popular stage play Iolanthe (unrelated to the Gilbert and Sullivan opera of the same title). Contemporary audiences would probably have been more familiar with the source material than I am and would know the answers to some of my questions, like is Ebn Jahia a villain? and is there some conspiracy to keep Iolanthe blind? and wait, who’s that other guy with the beard?

It’s shot on the same locations as the earlier Thanhouser film Romeo and Juliette (1911) and also shares some of its sets, but they’re still impressive here. The costumes are splendid taken on their own merit, but if I didn’t know the film was set in France, I would have guessed from the clothes that we were in Scotland. Almost the whole film is composed of medium-close shots that, compositionally, aren’t too interesting, but it’s decently edited together. The first reel is rather drawn-out, but the pacing improves tremendously in the second and third.

I don’t know. It isn’t bad, and I wouldn’t avoid watching it again, but I don’t think I’d strongly recommend it.

My rating: Meh.