Monthly Archives: January 2015

The Secret of the Palm (IMP, 1911)

The Secret of the Palm (IMP, 1911)

The Secret of the Palm (IMP, 1911)

Directed by Joseph Smiley

Starring Joseph Smiley and King Baggot

After the first viewing, I found The Secret of the Palm (1911) to be completely incomprehensible. I had no idea what it was even about, much less what was going on in the plot. I immediately watched it a second time, but was no less confused. I set the film aside for a while and came back later with fresh eyes, and still all I got from it was that seemingly unrelated things happen for no reason to people I have no idea who are, then some guy falls out of a palm tree and the film is over.

To Moving Picture News!

All right, IMP published a synopsis of their film in the trade journals to bamboozle entice exhibitors into booking it. According to their synopsis, the film is about a Spaniard named Don Alvarez (Joseph Smiley) who is sent to work on a fruit ranch in Cuba owned by Canby, a man his mother was school friends with. Canby’s daughter, Edna, is in love with Cecil Abbott (King Baggot), the ranch foreman. Don is “smitten by her charms” and jealous of the attention she shows to Cecil, so when Cecil goes into town to get the mail, Don stealthily steals the mail pouch and hides it at the top of a palm tree. Cecil is accused of the theft and is fired. Don is promoted to foreman. On the next mail day, Don gets a letter from his mother that said she sent him money in her last letter. Don scrambles up the tree to retrieve it, but falls afterward. He’s found by Cecil, who takes him back to the ranch, where he exonerates Cecil before dying.

I defy you to get any of that from the picture — even one single line. I’ve seen my share of incoherent films before, but I don’t think I’ve ever encountered such a nonsensical assemblage of scenes amounting to absolutely nothing. This makes As a Boy Dreams (1911) look like a masterpiece of filmmaking that’s brilliance will never be topped.

My rating: I don’t like it.

An Old Man’s Love Story (Vitagraph, 1913)

An O ld Man’s Love Story (Vitagraph, 1913)

ld Man’s Love Story (Vitagraph, 1913)

Directed by Van Dyke Brooke

Starring Norma Talmadge

Ethel Marsham (Norma Talmadge) lives in a state of “genteel poverty” with her parents. She’s in love with Cyril Moffat (Frank O’Neil), but he’s a poor man himself and her parents (James Lackaye and Florence Radinoff) are depending on Ethel marrying into wealth.

(I’m much more used to seeing Frank O’Neil in blackface. I didn’t recognize him at all with his natural skin tone and hair.)

James Greythorne (Van Dyke Brooke), Father’s old schoolmaster, has made a fortune abroad and is returning to America with the aim of settling down. He’s just the man Ethel’s parents are looking for. Ethel reluctantly agrees to marry him, but Greythorne isn’t blind and he realizes that her heart belongs to another.

Greythorne declares to Father that, on second thought, he’s much too old to marry his daughter, but he hopes that he’ll look favorably on his recently (very recently) adopted son and heir instead. He ushers him in and who should it be but Cyril.

The scenario is credited to W.A. Tremayne, who wrote for a large number of Vitagraph films as well as for the stage, but I couldn’t shake the feeling that the story seemed familiar as I was watching it. And then it hit me: Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s 1846 novel Lucretia. I wouldn’t go so far as to say it’s based on Lucretia, not even loosely, but it borrows some of its larger themes and a few specific situations, particularly the female lead hiding a message for her forbidden lover in the hollow of a tree at the edge of her parent’s land, which is lifted wholesale from Bulwer-Lytton.

Of all the pioneering studios, I like the films of Vitagraph most of all and I’ve seen a large number of them. When watching one, I like to play a little side game of connecting the props it uses to other Vitagraph films. In An Old Man’s Love Story, I noticed that the pergola in the Marsham’s backyard was previously used as the entrance to Vauxhall in Vanity Fair (1911), the rustic outdoor seating was used again in A Florida Enchantment (1914), and the tea set I believe is the same one seen in Fox Trot Finesse (1915).

The editing is crude and jumpy. There’s too much reliance on titles to move the plot. The lighting in the interiors is all overhead carbon arc or mercury vapor lamps, which is quite unflattering to the actors, but the outdoor scenes shot in natural light are much nicer. The set decoration is the usual for Vitagraph films of this vintage — namely, if one chair is good, then a dozen are surely better. It’s amazing the cast could navigate the maze of furniture squeezed onto every set. I don’t know who the cinematographer was, but they seemed to have an aversion to wide-angle lenses. Even for the exteriors, there’s nothing wider than a medium shot. Perhaps the aim was to make the story seem more intimate, but to me, it just feels claustrophobic.

Did I like it? Eh… my first impression was favorable, but after rewatching it to write this review and paying closer attention to the details, I have to say that it’s overall quite crudely put together. It’s a good story and well acted, Van Dyke Brooke’s performance being the stand-out, but I don’t think that’s enough to raise it any higher than…

My rating: Meh.

Across the Mexican Line (Solax, 1911)

Across the Mexican Line (Solax, 1911)

Across the Mexican Line (Solax, 1911)

Directed by Alice Guy-Blaché

I’ve had this 16mm reduction negative for some little time but paid little attention to it since, based on the title scribbled on the leader, I already had a copy of the film and had already transferred it to video. Still, eventually I got around to examining the reel and I quickly realized that it did not contain the film I thought it did. It was, in fact, a copy of Across the Mexican Line (1911), which is interesting because that film was presumed to be lost after the last known print of it was discovered to be unsalvageably deteriorated. I think any collector would say that it’s always a bit of a thrill to think that the film you’re holding is the only one in existence.

Across the Mexican Line was the first of Solax’s “Big Military Features” series of films. The release was “very timely” and “heartily” received by audiences, Moving Picture News reported in their film chart for April 29th, 1911. The picture was created to capitalize on the Mexican Revolution, which had just broken out the year before, and evidently it succeeded.

The film begins with Castro, a popular Mexican entertainer who sympathizes with the guerrillas’ cause, meeting with the commander of a detachment of Mexican troops. The commander needs intelligence of the American troop movements. Castro suggests that they use a female spy.

Dolores, the spy, ingratiates herself with Lieutenant Harvey and gains access to the telegraph room. Harvey even teaches her Morse code and shows her how the equipment works. Unfortunately for the Mexicans, Dolores fails in learning the information the commander wants. Castro tries a different, more direct approach: bribing Harvey. When that doesn’t work, he kidnaps him and takes him to the commander, who threatens the lieutenant with death unless he divulges the information.

Dolores, who has fallen in love with the man she was sent to spy on, sneaks out of the camp on a stolen horse and rides to the telegraph wires. She climbs a pole and taps into the wire, frantically messaging the American headquarters. The pursuing guerrillas shoot at her and she’s hit in the right hand, but continues tapping out the code with her left.

The Americans receive the message and a counterattack is launched. Just as Harvey is about to be shot by the firing squad, the Americans rush in and tear down the guerrilla fighters. Harvey embraces Dolores and the two kiss as the film ends.

Solax, in their ad copy, stated that they intended their Big Military Features to mark “a departure from the studio productions” that had dominated the screen and to instead be “big, lively, outdoor pictures, full of vigorous, active incidents”. Across the Mexican Line gets there, eventually, but the cramped, crowded sets of the first half are, to all appearances, very much a “studio production”. The editing style also adapts itself as the film progresses, from the long, continuous shots of the opening scenes to the short, staccato takes of the climax that rapidly cut between several simultaneous plot lines. It’s a dramatic change — going from shots that last around a minute and a half at the start of the film to just ten seconds at the end — and creates a feeling of heightening tension and of time running out.

Solax, in their ad copy, stated that they intended their Big Military Features to mark “a departure from the studio productions” that had dominated the screen and to instead be “big, lively, outdoor pictures, full of vigorous, active incidents”. Across the Mexican Line gets there, eventually, but the cramped, crowded sets of the first half are, to all appearances, very much a “studio production”. The editing style also adapts itself as the film progresses, from the long, continuous shots of the opening scenes to the short, staccato takes of the climax that rapidly cut between several simultaneous plot lines. It’s a dramatic change — going from shots that last around a minute and a half at the start of the film to just ten seconds at the end — and creates a feeling of heightening tension and of time running out.

Across the Mexican Line reverses the common damsel in distress trope. Harvey is the helpless one here, and it’s Dolores who must save him. Challenging gender roles was a common theme in Guy’s work, just as Guy herself challenged them in life. Even today, female directors are uncommon and are woefully underappreciated. When Guy began directing, she was quite literally the only one.

I liked Across the Mexican Line, but I will say that, until I read a contemporary plot synopsis, many of the details of the film were lost on me. It’s easy enough to get the gist from the picture alone — that Dolores is a spy, that Harvey is somehow important to Castro, and that Castro has some connection to the guy in the military costume — but everything else was nigh incomprehensible. It doesn’t help that the first scene, which the synopsis says introduced the military guy, is missing from my negative.

My rating: I like it.

Available from Harpodeon

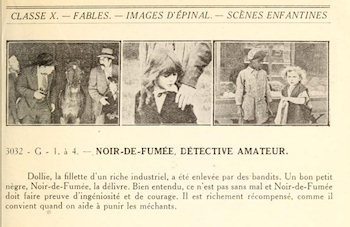

Noir-de-Fumée, Détective Amateur (?, 1931)

Noir-de-Fumée, Détective Amateur (?, 1931)

Noir-de-Fumée, Détective Amateur (?, 1931)

Directed by ?

Starring ?

To address the question marks, rather than posting in my standard form, I’ve decided to first take you on a little journey:

I mentioned before that I’m in the process of moving and I don’t have most of the film collection at hand. However, quite accidentally one title was left out and it’s been sitting on my make-shift desk for the last three months. It’s on four 60-foot bobbins of 9.5mm film. The title given on the bobbins is Noir-de-Fumée, détective amateur. It appears in the 1931 Pathé-Baby catalogue, item #3032.

But Baby releases were almost always re-titled, so what is this film really? Sometimes the catalogue listing will be of help: it might give the name of the star, or of the director, or rarely it will even reveal the original title. No such luck with Noir-de-Fumée, but there are a few clues. It’s in the children’s film section and is listed as a comedy. Also, it names one of the characters “Dollie”.

My first thought, based solely on this information, was that it’s a Baby Marie Osborne film. Pathé always called Osborne’s characters Dolly or Dollie, regardless of what the characters’ names were originally. The three screenshots are too small to tell who the actors might be, but one of them includes a black boy and that bears out the Osborne theory — Ernest Morrison frequently featured in her films. Trouble is, the description given didn’t match any of the Osborne films I was aware of, and after a quick scan of contemporary release notices and reviews available at lantern.mediahist.org for all of Osborne’s small oeuvre, none of them at all looked like contenders.

So, even if Osborne is out, maybe Morrison is still in. Pathé’s character naming might be an attempt to tie one of Morrison’s later works into his earlier output with Osborne. A Sunshine Sammy film, maybe? I know of them, but I’ve never seen one and I’m not familiar with their plots. Just glancing through a title list, it could be Rich Man, Poor Man (1922) or The Sleuth (1922). Those sound like appropriate titles for a film matching Pathé’s description.

I was leaning towards the Sunshine Sammy idea rather than what Morrison is most remembered for — Our Gang — simply because Noir-de-Fumée doesn’t fit at all with the sort of titles Pathé usually gave Our Gang films. Had it mentioned Négritina or Enfants, then yes, surely Our Gang, but it didn’t.

You might be asking why am I making this so difficult for myself — why don’t I just look up the item number in the Pathéscope catalogue at pathefilm.uk? That would list the original title along with Pathé’s. That works for earlier films, back when French Pathé-Baby releases and English Pathéscope releases were both printed at the same factory and shared the same item numbers, but not for films of this vintage. Further, Pathéscope mirrored most of Pathé-Baby’s output, but not all of it, and I could find nothing resembling an English version of this title.

You might be asking why am I making this so difficult for myself — why don’t I just look up the item number in the Pathéscope catalogue at pathefilm.uk? That would list the original title along with Pathé’s. That works for earlier films, back when French Pathé-Baby releases and English Pathéscope releases were both printed at the same factory and shared the same item numbers, but not for films of this vintage. Further, Pathéscope mirrored most of Pathé-Baby’s output, but not all of it, and I could find nothing resembling an English version of this title.

Well, that’s as far as I could get without biting the bullet and actually watching the film. Not that I didn’t care to see it, mind, but it was the difficulty of accomplishing this that I was avoiding. As for projecting it, I had my Gem with me, but that’s only for 9.5mm on reels — Noir-de-Fumée, as I said, is in bobbins and my Babies are boxed up. That left transferring it to video. It’s true that the components of my film scanner are here, but setting it up on the two banquet tables squeezed into this small apartment bedroom that I’m calling an office would be a challenge.

I avoided that challenge, as I said, for three months before curiosity won out over laziness. After transferring it, I saw at once that the male lead of the film was indeed Ernest Morrison. He plays Noir-de-Fumée (let’s call him Lampblack instead). The female lead character was called Boby (Bobbie). The Dollie (Dolly) that featured so heavily in the description doesn’t actually feature that heavily in the film. She’s kidnapped almost at once, and after that, she’s just a MacGuffin for Lampblack and Bobbie to rescue. (That’s an anachronism by the way — MacGuffin, I mean. The term more commonly in use in the silent era was weenie.) Dolly certainly isn’t Marie Osborne. Bobbie might have been — kids so young that they’re still chubby with baby fat are hard to tell apart — but I was reasonably sure Bobbie was played by Mary Kornman. That’s two Little Rascals (three actually, but I didn’t right away recognize Dolly as Peggy Cartwright). The Sunshine Sammy theory is looking shaky. The kidnappers are indistinct. A couple of them are in Snub Pollard getups but neither really looked like him otherwise. Paul Parrott was not to be seen, but there is a mule who I bet is named Dinah. The theory falls flat on its face.

Okay, so it’s an Our Gang film. Which one? Not so hard to find: “our gang” + “kidnap” = Young Sherlocks (1922), directed by Robert F. McGowan and Tom McNamara. Young Sherlocks was a very early entry to the Our Gang canon. Indeed, it was one of the first filmed. It was a two-reeler and Noir-de-Fumée is the equivalent of one reel, but the latter doesn’t seem to be severely edited because it’s actually just excerpting the imaginary sequence from Young Sherlocks with only minor edits and presenting it as a stand-alone film. That also explains the absence of the rest of the gang and probably why Pathé downplayed the connection to the series. It wasn’t released by Pathéscope because, in a way, it already had been. Pathéscope turned Young Sherlocks into three separate, much shorter films — Kidnapped, Comrades of the Crimson Clan, and Fun in Freetown — rather than release it in a single, longer form.

Maybe that was more than a “little” journey, but at any rate, we’ve arrived at our destination, so now let me talk about the film:

Dolly (Peggy Cartwright) is playing on the front lawn with her pony, Spinach, and an unnamed dog. A gang of bandits (Ed Brandenburg, Dick Gilbert, William Gillespie, Wallace Howe, and Mark Jones) appear and kidnap her, expecting to get $100,000 ransom from her rich papa (Charley Young). Across the street, Lampblack (Ernest Morrison) and his little friend Bobbie (Mary Kornman) witness the abduction and decide to intervene.

Dolly (Peggy Cartwright) is playing on the front lawn with her pony, Spinach, and an unnamed dog. A gang of bandits (Ed Brandenburg, Dick Gilbert, William Gillespie, Wallace Howe, and Mark Jones) appear and kidnap her, expecting to get $100,000 ransom from her rich papa (Charley Young). Across the street, Lampblack (Ernest Morrison) and his little friend Bobbie (Mary Kornman) witness the abduction and decide to intervene.

Lampblack and Bobbie follow the getaway car on their mule, Seventy-Five (Dinah). Spinach, who we’re told is a great friend of Dolly, follows as well, independent of the others, and catches up with the bandits first. They send him back with a note to Papa telling him where to bring the money. I imagine this took several takes and I also imagine why, given how cautiously the bandit gives the pony the note and how careful he is not to get his fingers anywhere near his mouth. Papa and Mama (Dot Farley) get the message and speed away in their car, stopping at the bank to withdraw a $100,000, which they seem to consider mere pocket change.

Meanwhile, Lampblack and Bobbie approach the hideout, but suddenly two bandits emerge and now they have to hide themselves. Bobbie squeezes down the barrel of a cannon (the bandits are prepared, we’re told) and Lampblack hides in a stack of cannon balls, his head sticking out the top but perfectly invisible (because he’s black and so are the cannon balls, you see). The bandits have come outside to smoke (polite of them). One tosses his still-lit match inside the cannon, where it lands square on the seat of Bobbie’s pants. As soon as they go back inside, she shimmies out and runs pell-mell across the countryside.

Lampblack sees Dolly tied to a tree, lackadaisically guarded by a bandit who seems to be more interested in the handsome man he sees gazing back at him in his looking glass. Lampblack picks up a shotgun and fires at the bandit, attracting the attention of the others. The kickback launches him into the air, landing on and knocking down one of the other bandits. He shoots again and likewise catapults himself into another.

Bobbie runs to a gas station and sits in a bucket of water. Papa and Mama are there refueling. Dripping wet, she walks over and lets them know where Dolly is being held. They pick her up into the car and speed off without even paying for their gas.

Back at the hideout, the bandits have got the upper hand on Lampblack. He’s backed up against a telegraph pole and they’re throwing swords at him. Every one narrowly misses Lampblack and strikes the pole, eventually causing it to snap in half and come tumbling down on them. Seventy-Five appears to lend assistance, kicking cannon balls at the bandits (he has remarkable aim, you know).

The day is won and Lampblack unties Dolly. Just then, Papa, Mama, and Bobbie pull up. Papa, so pleased with the kids’ efforts, gives them the $100,000, and golly gee, what candy we could buy wit’ all dis dough.

I’m not big on child comedies, mostly because they star child actors. Mary Kornman doesn’t do much besides stand around and squint. Peggy Cartwright, as I said, is hardly in the film. In the few scenes where she’s not tied up, she does moderately well exhibiting the correct emotion, but her timing is atrocious. I will say, however, that Ernest Morrison is a natural. He acts believably as the kid who starts out on an adventure half-playing pretend and then finds himself in over his head when it gets real (it’s a slapstick comedy, yes, but he does manage to mix in some pathos — he’s the only one who does, in fact, including the adult actors).

I’m not big on child comedies, mostly because they star child actors. Mary Kornman doesn’t do much besides stand around and squint. Peggy Cartwright, as I said, is hardly in the film. In the few scenes where she’s not tied up, she does moderately well exhibiting the correct emotion, but her timing is atrocious. I will say, however, that Ernest Morrison is a natural. He acts believably as the kid who starts out on an adventure half-playing pretend and then finds himself in over his head when it gets real (it’s a slapstick comedy, yes, but he does manage to mix in some pathos — he’s the only one who does, in fact, including the adult actors).

My rating: Without Morrison, I would say dislike, but he elevates it to a solid meh.

Available from Harpodeon